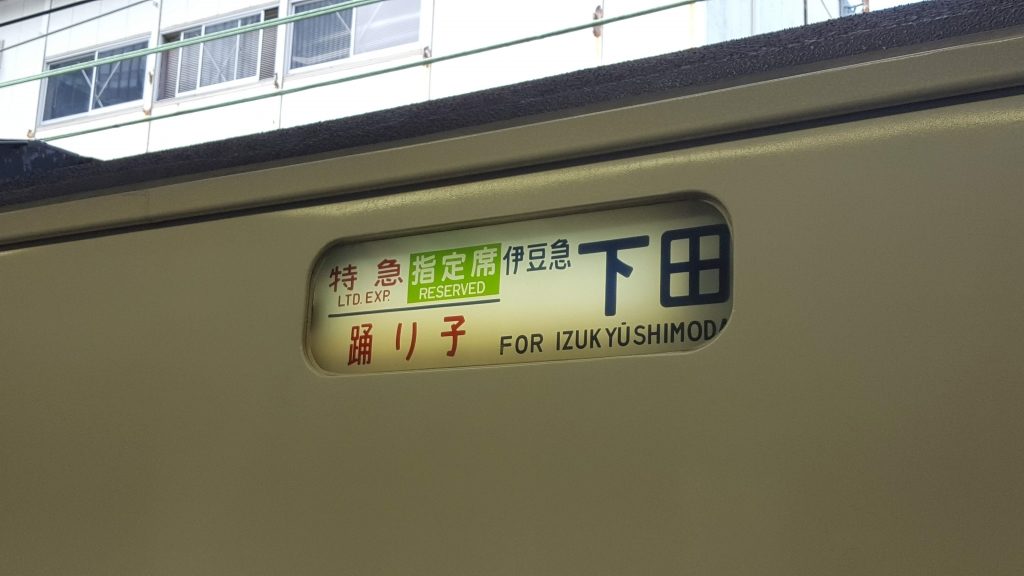

After a few more days spent in Tokyo, including a hilariously bad date that I’ll carve into a short story one day, I headed off to the Izu Peninsula. My first Workaway position was set up in Shimoda (the end of the train line on the southern coast), but on recommendation from my soon-to-be hosts I’d booked in for 2 days at K’s House in Ito, so off I headed on the Limited Express from Tokyo Station. If you want to take a train anywhere in Japan, the best place to find information is Hyperdia where you can search over a huge range of criteria so you can find the best deal. I didn’t find this out until I met my amazing housemates in Kisami, who’d been in Japan much longer than me; so on the day I left for Ito, I just went to the JR desk at Tokyo station and said “one ticket to Ito, please”.

“Would you like a seat reservation?” the lady asked.

“Do you think I need one?” I replied, having flashbacks to the hundreds of hours I have spent on British trains standing, crouching, perched on my luggage or in a luggage rack.

“If you don’t have one, you might not get a seat.” She smiled. The seat reservation was an extra 1500 yen. I took it.

The train rolled out of Tokyo and through suburbs in the twinkling spring sun. It felt like a voyage into the unknown, so new and fresh and promising as Tokyo’s sprawl gave way to fields and valleys and little coastal resort towns nestled in bays cupping a sapphire sea. It was so beautiful that it entirely squashed the bitterness I felt over having been sold a seat reservation for a train carriage that had less passengers than a full family car. I watched the spring sky flip flop from perfect sun to gloomy clouds and back again; seemingly switching season with each tunnel we sped through. At Ito I was greeted with rain on the short walk from the station to my ryokan.

Hundreds of years ago, an English guy by the name of William Adams landed in Japan, met and befriended Tokugawa Ieyasu (who by now was shogun), settled down in Ito, taught the Japanese how to make Western style ships, and generally became as naturalised in Japan as possible. Perhaps it was just the sunset over the mountain making my heart soar as I checked out the small beach-front sculpture park, but something about being in the same place centuries later filled me with hope. If he could learn the language fluently before the days of Duolingo, mass printed textbooks, and SRS systems, there was hope for me yet. That night I slept in a futon for the first time, soothed to sleep by the cozy smell of tatami and the gentle rain against the window.

The next day was one of glorious sunshine and I intended to make the most of it. I set out walking along the coast with the wind at my back and the sea at my side. The combination of dazzling sun on the palm flanked strip that led to a small marina brought to mind Miami or Venice Beach rather than Japan.

I fully embraced my time as a tourist; eating too many snacks, and even splashing out on a glass bottom boat trip where I was soon reminded that the temperature on shore in the sun is no solid indication of conditions out in the path of the sea-breeze and salt spray. Two chihuahuas huddled inside their owner’s coat as I looked on jealously. We saw next to nothing in terms of underwater sealife from the submerged windows, but out on the water the boat staff sold packs of expired shrimp crisps for 100 yen each and encouraged passengers to fling them at the mob of seagulls and hawks who followed along behind. As far as paid interactions with wildlife go, it seemed pretty harmless, so I joined in, glad to have not brought along the kind of person who would tut about feeding vermin.

Back on land and in the mood to explore, I decided to keep walking along the coast to the next town, Usami, just to see what was there. Outside of a bookshop sat the nastiest looking vending machine I have ever seen- covered in rust and dispensing porno mags, it looked like a prop from a show where they needed to quickly establish the mis-en-scene of a very very bad part of town. Alongside it, two children played, jumping back and forth between the automatic bookshop doors. I moved on. There didn’t seem to be much to Usami, just a handful of shops and little cafes, until looking upwards across from the ocean I caught sight of a streak of white against a dark green forest surround. A huge statue of Buddha. He smiled out at me from a hillside in a way that said “come and see me”. I checked my phone maps. The temple, Usamikannon, was at the top of a winding road, maybe 7 or 8km away. It seemed doable. All I had to do was keep Buddha in my sights and walk.

This did not prove to be as easy as I thought, thanks to a small winding river and train line crossing the town as I headed inland and uphill, and the simple fact that once on a slope it is not always possible to keep things further up the slope in view. I got briefly lost in a car park. I crossed the river five times. I briefly trapped myself alongside the tracks and had to follow them for far too long to find a crossing. Eventually I was spewed out of the edge of town onto a main road; steep and flanked by stalls selling bags of oranges for thousands of yen, while other oranges lay in the road and were pecked at by crows. The sun was relentless on my back as I wound my way past a brewery and roadworks, ever ascending away from the sapphire sea which now seemed so far away. Even out of my jumper, the sweat felt like it was pouring off me. A click or two from my goal the pavement disappeared, but I refused to stop, clinging to the edge of the road as I hiked on with shrubbery whipping at my face, the cars and lorries whizzing past with only a handful of centimetres to spare.

And then there he was, just across the road, as serene and smiling as he’d been two hours before. I crossed, took a moment to find the route to the entrance and walked up to the temple gate.

It was closed. I pushed against it. No budge. I walked around the gate just to check. There was what looked like a little ticket booth, but no one was around. I sat down on a flimsy green plastic bench and took off my shoes to let the sun dry the sweat from my socks, drank the last of my water and checked my phone maps again. Google was convinced there was a footpath that came out at the back of the temple and lead all the way down to Usami.

Safety was on my mind as I took it. Yes, rather than walk alongside the busy dangerous road on my descent risking heat exhaustion, I would stroll down a mountain footpath under dappled light, surrounded by bird song. This vision started to waver as I passed an abandoned car, decaying under a tree. The air felt still and strange, and heavy with silence. After about 15 minutes of walking, I came across a collection of shacks, built from corrugated iron and tarps, covered in moss and surrounded by beer bottles. Just as I started to feel rather uneasy, the trail ceased to be. Ahead of me was only light brush, by no means impossible to traverse but unclear. The survival part of my brain was starting to flash up red warning signs reminding me of everything that could possibly harm me, and for once it didn’t seem overplayed. Not a soul on earth except me knew where I was right now. Even leaving aside the worrying question of who lived in those shacks and where were they right now, there were venomous snakes (of which Japan has a handful), wild boar, and the very real possibility of getting lost and not finding my way before nightfall to consider.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, and then regretted it, turned around and walked back the way I came. When I finally returned to the sweet beautiful embrace of K’s House Ito and soaked away my aches in one of the private onsen baths, I worked out how far I’d walked in the day. What had started as an innocuous stroll had morphed into a 22km hike.

The next morning it was time to leave Ito and K’s. If you’re ever travelling around the Izu Pennisula and need somewhere to stay, I definitely recommend it. They advertise themselves as a hostel ryokan, which essentially means an affordable authentic experience of tatami rooms, futons, gorgeous natural wood, public and private onsen, a melange of staircases that have a magical edge to them, and an unbeatable view out over the river from the common areas. As I ate my breakfast sat on the tatami with the soft spring sunshine streaming in, I looked out at the little birds flitting across my view and drank in the moment. A kingfisher hunted down his breakfast while large koi swam in lazy circles, too large to fear the little blue flash. Out on the veranda two tits tilted their heads from their perch on an immaculately pruned red maple; visitors to a gallery scrutinising a painting- “British girl with Japanese breakfast”.

Hey there! Do you enjoy reading about my travels? Want to show your appreciation?

Help a wanderer out with a donation- paypal.me/RumadeRu

All contributions are very gratefully received!